The recent shutdown of Samourai Wallet and the arrest of its co-founders have sent ripples throughout the cryptocurrency community, raising critical questions about the future of privacy and self-custody in the digital asset space. This article delves into the details of how Samourai Wallet operated, the reasons behind the U.S. authorities’ actions, and what this signifies for other privacy-focused crypto tools.

The Arrest and Indictment of Samourai Wallet Founders

In April, Samourai Wallet’s co-founders, Keonne Rodriguez and William Lonergan Hill, were arrested and charged with money laundering and operating an unlicensed money-transmitting business. Rodriguez pleaded not guilty and was released on bond, while Hill awaits extradition from Portugal.

Following the indictment, the FBI issued a warning against using unregistered cryptocurrency money-transmitting services, hinting at a potential future where U.S. regulators might mandate money transmitter licenses for even non-custodial crypto tools.

How Samourai Wallet Enhanced Privacy

Samourai Wallet distinguished itself with privacy-enhancing features, primarily Ricochet and Whirlpool, an implementation of CoinJoin. These tools aimed to obfuscate transaction origins and destinations, making it harder to trace the flow of funds on the blockchain.

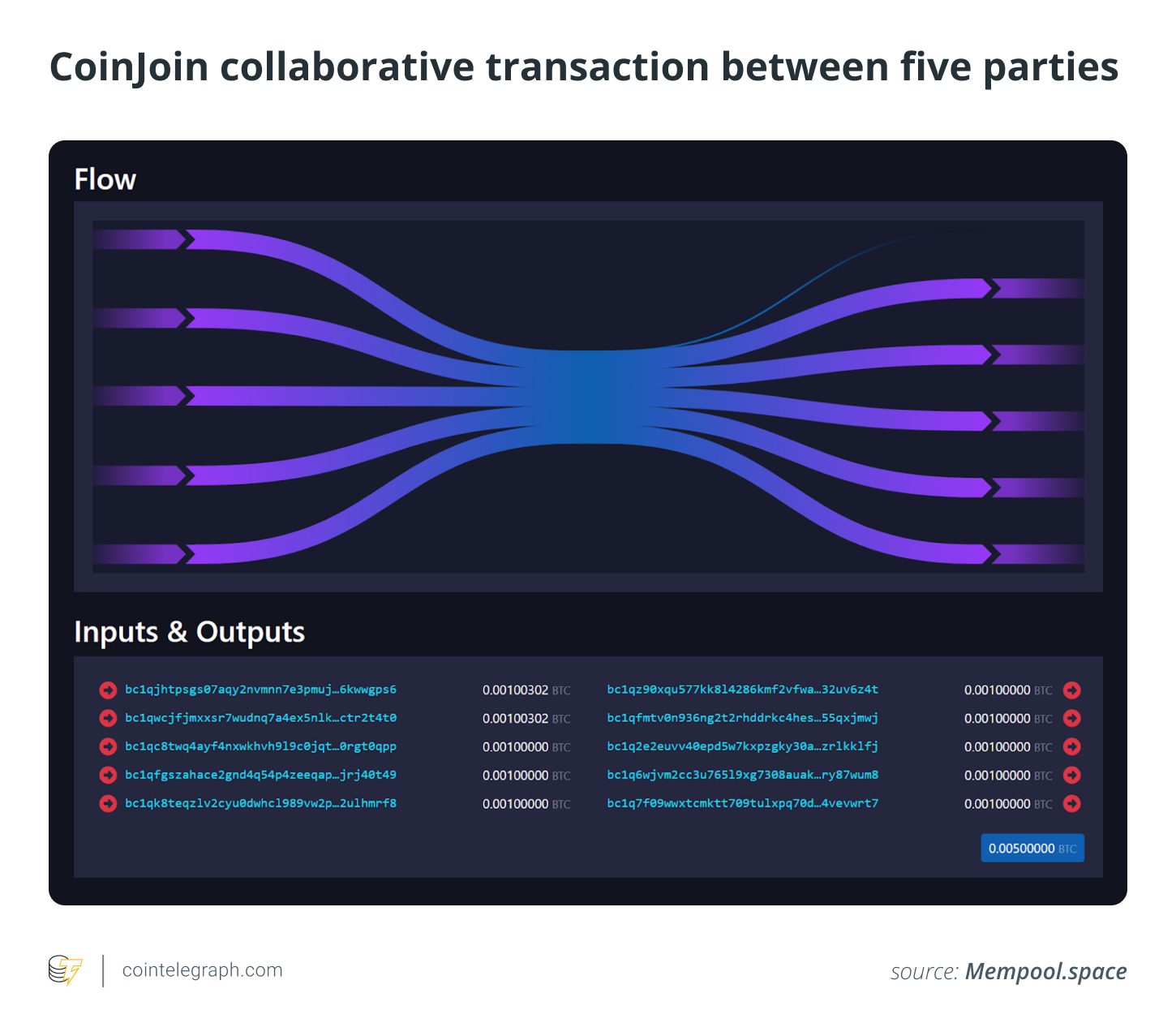

CoinJoin transactions pool inputs and outputs from multiple users, creating a mix of identically sized transactions that obscure ownership. Blockchain analysts find it significantly challenging to track funds after they’ve been processed through a CoinJoin.

Whirlpool, Samourai Wallet’s CoinJoin service, used a coordinator server to facilitate these transactions. Users’ wallets would submit input and blinded output addresses, with the server verifying participation anonymously. This process ensured that the server could validate the legitimacy of participants without knowing the exact input they contributed.

Unlicensed Money Transmitting Business Allegations

The core of the legal issue revolves around whether Samourai Wallet operated as an unlicensed money transmitting business, violating 18 U.S. Code § 1960. This law applies to those who control or manage an unlicensed money transmitting business.

While Samourai Wallet was a self-custodial wallet with no direct control over user funds, the prosecution argues that its operation of Whirlpool, a service facilitating the transfer of cryptocurrency, qualifies it as a money transmitter. This is despite the fact that the wallet couldn’t control funds or conduct transactions on behalf of its users.

A key argument against Tornado Cash offers a relevant comparison, stating that a money transmitter is “any other person engaged in the transfer of funds,” irrespective of control over those funds. This interpretation broadens the scope of what constitutes a money transmitter and could have significant implications for other decentralized crypto tools.

The court cited the Merriam-Webster dictionary, explaining “transfer” is the conveyance of right, title, or interest in real or personal property from one person to another.

The Role of Profit and Financial Gain

The profits generated from Whirlpool are legally significant. FinCEN guidance indicates that software providers enabling untraceable transactions are anonymization service providers, not money transmitters. However, if they “engage as a business in the acceptance and transmission of value” for financial gain, they are considered money transmitters. This distinction hinges on whether the activity is an “ongoing enterprise carried out for financial gain.” Samourai Wallet’s charging of fees for Whirlpool usage is a core reason it is facing these money transmitting charges.

Money Laundering Accusations

Samourai Wallet’s founders also face money laundering charges, potentially leading to 20-year prison sentences under 18 U.S.Code § 1956(a)(1). To be charged with money laundering, a defendant must conduct a financial transaction, being aware that the property involved is the proceeds of some unlawful activity.

Prosecutors point to Samourai Wallet’s marketing of the platform to “Dark/Grey market participants” as evidence that they knew and encouraged the flow of illicit funds. While users’ wallets generated addresses themselves, they state it is not needed that they have control over the addresses involved. The prosecution states that Samourai operated a centralized server that created the new BTC addresses used during the transactions. The users wallets generate the addresses themselves, and the server can only verify that the address submitted for withdrawal was provided by one of the participants of Whirlpool.

The accusations against Samourai Wallet suggest an attempt to extend legal responsibility for laundered funds to non-custodial products if server infrastructure is involved.

Implications for Privacy Tools and Self-Custody

The Samourai Wallet case has significant implications for the future of cryptocurrency privacy tools and self-custody solutions. The potential classification of privacy-enhancing tools as money transmitters could stifle innovation and limit access to these essential services. Some implications:

- The case could lead to stricter regulations for non-custodial wallets and mixing services.

- Developers may face increased scrutiny and potential legal risks for creating privacy-focused tools.

- Users could have limited access to tools that protect their financial privacy.

The implications are vast, with many worrying about the effect that this will have on the future of on-chain privacy, as well as Bitcoin itself. The outcome of this case could shape the regulatory landscape for cryptocurrency privacy tools for years to come.

However, it is also important to remember that code hosted on a Git repository is protected by the First Amendment. If the case simply consists of code hosted on a Git repository, then the distribution of privacy tools is protected by First Amendment rights in the United States.